SM Abstract Base Class

An abstract base class in Python is a class that cannot be instantiated and serves as a blueprint for creating subclasses, defining common methods, and enforcing specific behavior.

You can refer further to the optional reading on Abstract Base Class.

Goals

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Define output function and next state function

- Draw state transition diagram and time-step table

- Implement output function and next state function inside

get_next_valuesoverridden method.

start state, get_next_values, next state, current state, abstract base class, abstract method

Designing StateMachine Class

As mentioned previously, all state machine have some common characteristics. This motivates us to design an Abstract Base Class for State Machine. In designing an Abstract Base Class for state machine we try to identify what is the thing that all state machines have. We know that all state machine has a state. This shall be one of our attributes. We also try to figure out what all state machines can do in common. What are the common operations? For our design, we will create three methods that all state machines can do:

start()which is to start the state machine by applying the initial state to the current state of the machine. Before calling thestart()method, a state machine would have no state and cannot be run.step(inp)which takes in the current input of the machine and moves the machine to the next state in the next time step. This method returns the output of the machine at that time step.transduce(list_inp)which takes in the list of all the inputs. This method simply calls thestart()method and runstep()for all the input in the list of the input argument.

Our StateMachine class is an Abstract Base Class. This means that some of the methods of this class are waiting for implementation in the child class. This StateMachine class itself should not be instantiated. Any state machine instantiation should be done from one of the child classes of StateMachine. Why is this so?

The reason is that every state machine has different initial state and different output function as well as next state function. If two state machines have the same initial state as well as the same output and next state functions, it means that the two machines are equivalent. Therefore, StateMachine class cannot provide the detail of what is the initial state of a state machine nor can it provide the functions for the output and the next state of a state machine. These must be defined in the child class definition. The abstract StateMachine class only contains those implementations that is found common for all state machines. In defining our Abstract Base Class, we can specify that any implementation of its child class must define the implementation of certain methods. This is done in Python using @abstractmethod decorator. In our case, we will force child classses of StateMachine to define a method called get_next_values(state, inp) where these sub classes can define the implementation of the output and next state functions. This means that this method should return two things, the output and the next state given the current state and the current input.

Let's draw the UML diagram of the StateMachine class.

In this class diagram, we identify that StateMachine is an abstract class which requires another sub class to implement some of its definition. We also specifies using <<abstract>> notation that it is the get_next_values(state, inp) that the sub class has to define. Note also that the start_state must be initialized by the sub-class also since each state machine may have different initial state.

Recall that get_next_values(state, inp) in the child class provides the implementation of both the output and the next state functions. These functions are needed by the step(inp) method which is inherited from StateMachine class to determine the output and change the current state to the next state. Let's see how we can implement this in Python.

Python Implementation of Abstract Base Class

Python has a module called abc which can be used to implement an Abstract Base Class. Any Abstract Base Clas should inherit from ABC class inside the abc module (yep, the class name uses capital letters while module name uses small letters in Python).

from abc import ABC

class StateMachine(ABC):

pass

abc module provides a decorator @abstractmethod which we can use to enforce that some method has to be implemented in the sub class.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class StateMachine(ABC):

def start(self):

self.state = self.start_state

def step(self, inp):

ns, o = self.get_next_values(self.state, inp)

self.state = ns

return o

@property

@abstractmethod

def start_state(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

pass

# cannot instantiate StateMachine class

# this will generate error

s = StateMachine()

If you try to instantiate an abstract class with some abstract method, Python will complain and throws an exception.

In the above implementation, we also define start() method as simply applying the start_state as the current state value of the machine. In this case, self.start_state is the computed property and we have defined this property to be an @abstract_method. This means that the child class has to define this computed property to return the starting state of the State Machine. Moreover, the step(inp) calls get_next_values(state, inp), which should be implemented in the child class, to get the next state and the output given the current state and the current input. The next state is then applied to the state and the step() method returns the output. Similar to start_state, the method get_next_values(state, inp) is declared as an @abstractmethod. This means that the child class is responsible to implement the method's definition. It only makes sense that the starting state and the state transition diagram, defined in the get_next_values(), are implemented in the child class. The reason is that every state machine has different starting states and transition diagrams and it is not possible to capture these in the abstract base class.

Thus, step() is designed to update the state of the state machine. Thus, when get_next_values() is implemented, it must be implemented as a pure function.

Creating a LightBoxSM Class

In our previous notes, we discussed the light box state machine. We simulate it using Object Oriented Programming by defining a class. But now, we have an abstract class from State Machine. How can we create this same light box state machine without re-writing the codes that is already contained in the class StateMachine? First, let's recall how we wrote the LightBox class without inheriting StateMachine class.

class LightBox:

def __init__(self):

self.state = "off"

def set_output(self, inp):

if inp == 1 and self.state == "off":

self.state = "on"

return self.state

if inp == 1 and self.state == "on":

self.state = "off"

return self.state

return self.state

def transduce(self, list_inp):

for inp in list_inp:

print(self.set_output(inp))

lb1 = LightBox()

lb1.transduce([0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1])

Notice a few things. The class above has an attribute called state which store the state of the state machine. The set_output() method is similar to step(inp) and get_next_values(state, inp) methods since they provide the output and affect the state of the machine.

In using the StateMachine class, we will use inheritance and only define two things:

start_statecomputed property which has to be defined to return the machine initial state value, andget_next_values(state, inp)method which provides the output and next state functions.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class StateMachine(ABC):

def start(self):

self.state = self.start_state

def step(self, inp):

ns, o = self.get_next_values(self.state, inp)

self.state = ns

return o

@property

@abstractmethod

def start_state(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

pass

class LightBoxSM(StateMachine):

@property

def start_state(self):

return "off"

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

if state == "off":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "on"

else:

next_state = "off"

elif state == "on":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "off"

else:

next_state = "on"

output = next_state

return next_state, output

lb2 = LightBoxSM()

lb2.start()

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(1))

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(1))

print(lb2.step(1))

print(lb2.step(1))

print(lb2.step(1))

print(lb2.step(0))

print(lb2.step(1))

Notice that we have produced the same output using a different way of writing the light box state machine. It would be convenient to have something like the transduce() method where we can just put in a list of input to the machines and produce the output. You will work this method in your problem set.

Another thing, you may want to note is that the class LightBox has to implement the computed property start_state and get_next_values(). When the child class does not have have these implementation, it will throw an exception.

Designing a State Machine

In this section we will discuss how we can design a state machine and write its implementation in Python using some of the code we have provided such as in our StateMachine class.

Is this a state machine?

The first step is to ask whether our computation is a state machine. To determine the answer for this question, we ask a few question?

- is the output a function of the current input only or it a function of its history or state as well?

- does the computation requires me to remember something else besides knowing the input arguments or can I determine the output solely from the input arguments?

If your computation output is a function of not only the input arguments but also its history or state of the machine, then it is a state machine.

What is the state of the machine?

Once we know that it is a state machine, we should ask what the state of the machine is. To find out what the state is, we can ask the following questions:

- what is the thing that I need to remember?

- what is the thing I need to know besides my input arguments in order to determine the output?

Is the state finite?

Once we know what the state is, we can determine whether the state is finite or not. Later on we will show that this answer may affect how we determine its output and next state function.

Determine the output and next state functions

If there is finite state, this step involves drawing the state transition diagram based on the problem specification. On the other hand, if the state is not finite, we can use another technique like time step table to try to figure out what is the output and next state function.

Implementation

Once all those steps done, we can implement them in Python. We do this by doing the following:

- Create a new class inheriting from

StateMachineclass - Initialize the

start_state - Define

get_next_values()

The implementation of get_next_values() follows closely the previous steps. If one has a state transition diagram, every arc and arrow in the diagram is one if condition.

Using the Steps for LightBoxSM

Let's use the steps above and see how we come up with the implementation of LightBoxSM. First, we ask whether it is a state machine. Since the output not only depends on whether the button is pressed or not (input is 1 or 0) but also on how many time the button has been pressed, we are dealing with a state machine. We can see this since it is not enough for us to determine whether the light is on or off simply from knowing whether the button is pressed or not. We need to know the "other" information.

Second, we ask what is the state by asking what is the thing that we need to remember. In this case, we need to remember whether currently the light is on or off when the button is pressed. So the status of the light, which is either "on" or "off", is the state of the machine.

Third, we ask is the state finite? In this case the answer is yes. The reason is that we only identify two states, i.e. "on" or "off".

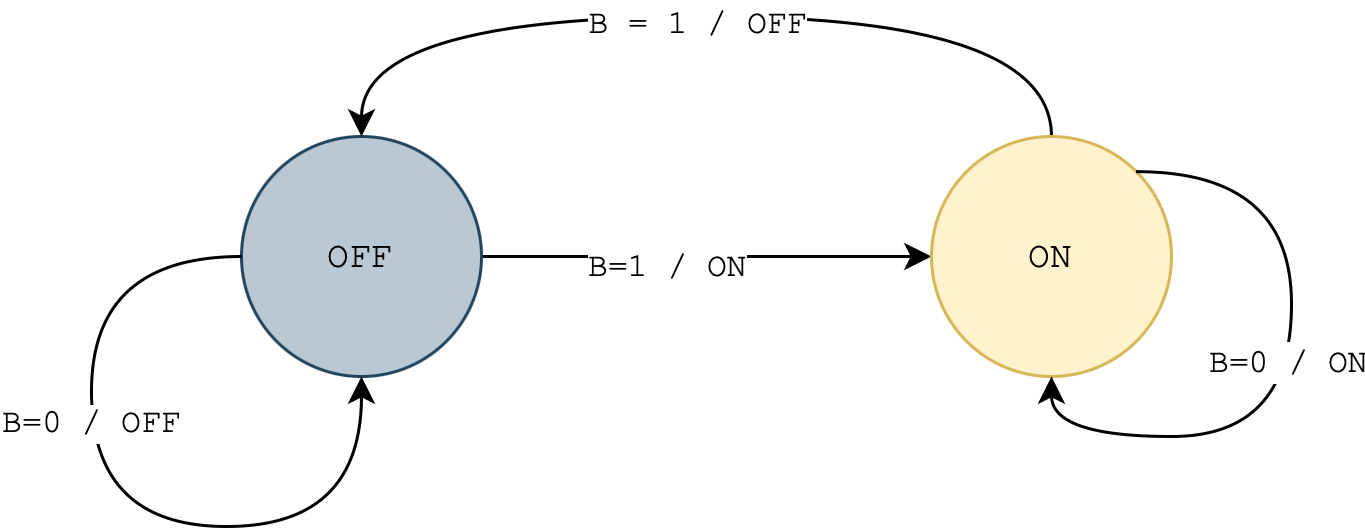

Fourth, we draw the state transition diagram based on our problem formulation. A figure of our state transition diagram is shown below.

The states are represented by the circle and we have only two states, i.e. "on" and "off". The arrow direction tells us the next state function. Given the current state and the input value, we know what is the next state by looking at the arrow direction. Furthermore, each arc is labelled with an input and its output. So for example, B=0/OFF on the most right arrow means that when the current state is "off" and the input 0, the output is "off" for that transition. This provides the output function.

Once we have the state transition diagram, then we can begin to write its Python implementation. First, we need to define the start_state computed property. In our case "off" is the initial state of the machine.

class LightBoxSM(StateMachine):

@property

def start_state(self):

return "off"

In the above definition, we declared start_state as a property using Python decorator. This computed property returns the value of the initial state of the machine, which in this case is off.

Next, we define the get_next_values(state, inp) from the state transition diagram. Notice that there are four arrows in the diagram. So we should expect to have four branches in our if-else statements.

class LightBoxSM(StateMachine):

@property

def start_state(self):

return "off"

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

if state == "off":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "on"

else:

next_state = "off"

elif state == "on":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "off"

else:

next_state = "on"

output = next_state

return next_state, output

In the case here, it happens that the output function is the same as the next state function. But this is not necessarily the case in general. But looking at the state transition diagram will help us to determine both its output and next state functions.

Notice that get_next_values(state, inp) must always return two things: next_state and output. This is needed by the step() method in the StateMachine class.

def step(self, inp):

ns, o = self.get_next_values(self.state, inp)

self.state = ns

return o

If the get_next_values() only returns one thing, Python will throw an exception because it expects a tuple of two items.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class StateMachine(ABC):

def start(self):

self.state = self.start_state

def step(self, inp):

ns, o = self.get_next_values(self.state, inp)

self.state = ns

return o

@property

@abstractmethod

def start_state(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

pass

class LightBoxSM(StateMachine):

@property

def start_state(self):

return "off"

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

if state == "off":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "on"

else:

next_state = "off"

elif state == "on":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "off"

else:

next_state = "on"

output = next_state

# trying returning only one item

return next_state ##, output

lb2 = LightBoxSM()

lb2.start()

print(lb2.step(0))

Run the code above, and you will find that Python says "too many values to unpack" and it expects two items from get_next_values(). We can give more explanation by catching this error using try and except block in Python. So our design requires that get_next_values() returns both the next state and the output.

class LightBoxSM(StateMachine):

def __init__(self):

self.start_state = "off"

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

if state == "off":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "on"

else:

next_state = "off"

elif state == "on":

if inp == 1:

next_state = "off"

else:

next_state = "on"

output = next_state

return next_state, output

Try out the fixed get_next_values in the live codeblock above and confirm that there's indeed no more error triggered.

Designing Accumulator Class

We will show one more example on how to design a state machine. This time, we would like to create an AccumulatorSM. This state machine simply accumulates the input. The input to this machine is any number. The following is a typical example of input and output of an accumulator.

acc = AccumulatorSM() # in the beginning it's zero

acc.step(10) # outputs 10

acc.step(25) # outputs 35

acc.step(-5) # outputs 30

acc.step(11) # outputs 41

acc.step(-41) # outputs 0

Let's follow the step to design this machine. The first step is to ask whether this is a state machine. The answer is affirmative because we cannot determine the output solely from the input. We have to remember what is the accumulated value up to this point in time.

Second, we ask what the state is. What is the thing we have to remember? In this case is the accumulated value. To determine the output, we not only need to know the input to the machine but also the current accumulated value in the machine. This is the state of the machine.

Third, we ask whether the state is finite. The answer is negative this time. The reason is that there infinite possible values of the state or the accumulated value. The accumulated value can assume any number like 10, 35, 30, 41, 0, 11, 100, 100.5, etc. It can take any values and so this time, it is not possible to draw the state transition diagram. The reason that it is not possible is that state transition diagram is feasible only if the number of state is finite, which is not the case of an accumulator.

How can we determine its output and next state function? One useful tool is to fill in the time step table. We show such table in the example below.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current state | 0 | 10 | 35 | 30 | 41 |

| current input | 10 | 25 | -5 | 11 | -41 |

| next state | 10 | 35 | 30 | 41 | 0 |

| current output | 10 | 35 | 30 | 41 | 0 |

In the time step table, the columns are the different time steps like time 0, 1, 2, 3, etc. There are four rows in this table. The first one is the "current state". The value of this row at time step 0 is the initial state of the machine. In our case above, it is 0. The next row gives you the different input at different time steps. Our job now is to fill in the "next state" and the "current output" rows.

Notice that the next state value at time is the same as the current state value at time . How do we fill up the row "next state"? There is no clear step-by-step answer. One way is to identify first what is the state. Again, the state is the thing that the machine has to remember, the information needed besides the current input in order to determine the output and the next state.

For example, if we look at time step 2 and ignoring the current state value 35, we should ask, given the current input -5, what is the information I need to get the output 30? Answering this question will help us to identify we need to know the accumulated value up to this point, which is the value of the current state, i.e. 35. Knowing the accumulated value 35 and the current input -5, it is straight forward to obtain the output of that time step by adding the two . This output is the new accumulated value in the machine and, therefore, is the information that is needed at time step 3. This is why it is set as the next state value.

If we can fill up the time step table, hopefully we can try to figure out the next state and the output functions by asking:

- How do I determine or compute the output from the current state and the current input?

- How do I determine or compute the next state value from the current state and the current input?

In this case, the output and the next state is the same and can be computed simply by adding the two:

Knowing the output and next state functions enable us to write the implementation in Python. Similar to the LightBoxSM example, we simply need to specify two things:

start_stateandget_next_values()

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class StateMachine(ABC):

def start(self):

self.state = self.start_state

def step(self, inp):

ns, o = self.get_next_values(self.state, inp)

self.state = ns

return o

@property

@abstractmethod

def start_state(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

pass

class AccumulatorSM(StateMachine):

@property

def start_state(self):

return 0

def get_next_values(self, state, inp):

output = state + inp

next_state = output

return next_state, output

acc = AccumulatorSM()

acc.start()

print(acc.step(10)) # outputs 10

print(acc.step(25)) # outputs 35

print(acc.step(-5)) # outputs 30

print(acc.step(11)) # outputs 41

print(acc.step(-41)) # outputs 0

Start Method in StateMachine Class

It is important to call the start() method before running step(). The reason is that the state machine's state is initialized with the starting state only at the call of the start() method. Let's try what happens if we call step() without first calling start().

acc = AccumulatorSM()

# acc.start()

print(acc.step(10)) # outputs 10

print(acc.step(25)) # outputs 35

print(acc.step(-5)) # outputs 30

print(acc.step(11)) # outputs 41

print(acc.step(-41)) # outputs 0

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-29-234b6b850979> in <module>

1 acc = AccumulatorSM()

2 # acc.start()

----> 3 print(acc.step(10)) # outputs 10

4 print(acc.step(25)) # outputs 35

5 print(acc.step(-5)) # outputs 30

<ipython-input-22-556607471350> in step(self, inp)

8 def step(self, inp):

9 try:

---> 10 ns, o = self.get_next_values(self.state, inp)

11 except ValueError:

12 print("Did you return both next_state and output?")

AttributeError: 'AccumulatorSM' object has no attribute 'state'

Python produces and error saying that the AccumulatorSM object has no attribute called state. The reason is that the attribute state is only created and assigned inside the method start(). Recall in our class definition how the method is implemented.

class StateMachine(ABC):

def start(self):

self.state = self.start_state

What's the purpose of this method? Why can't we just initialize the state attribute inside __init__(self) of the StateMachine class?

The reason is that __init__() is only called once during object instantiation. On the other hand, creating another method called start() allows us to call this method again in the event that we wish to "restart" the state machine back to its original state. Consider the following example.

acc = AccumulatorSM()

acc.start()

print(acc.step(10)) # outputs 10

print(acc.step(25)) # outputs 35

print(acc.step(-5)) # outputs 30

print(acc.step(11)) # outputs 41

print(acc.step(-41)) # outputs 0

# restart machine

acc.start()

print(acc.step(100)) # outputs 100

print(acc.step(10)) # outputs 110

10 35 30 41 0 100 110

Having such initialization outside __init__() allows this flexibility of restarting the state of the machine.