By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Explain and implement breadth first search

- Explain and implement depth first search

Important words:

- graph traversal

- breadth first search

- depth first search

- topological search

- distance

- colour

- parent vertex

- start/finish time

Introduction

In the previous lesson, we have introduced how we can represent a graph using object oriented programming. We created two classes Vertex and Graph. One main use cases with this kind of data is to do some search. For example, given the graph of MRT lines, we would like to search what is the path to take from one station to another station. We usually are interested in the shortest path. This is what Google Map and other Map application does. In this lesson, we will discuss two graph search algorithms: breadth-first search and depth-first search.

To do these algorithms, our Vertex class and Graph class may need some additional attributes to store more information as it performs the search. One way to modify our classes is to create a new class. However, we would like to introduce the concept of Inheritance. Inheritance allows us to re-use our existing class and create a new class that is derived from our existing class. Therefore, to implement our search algorithm, we will use inheritance to modify our existing Vertex and Graph classes.

Breadth First Search

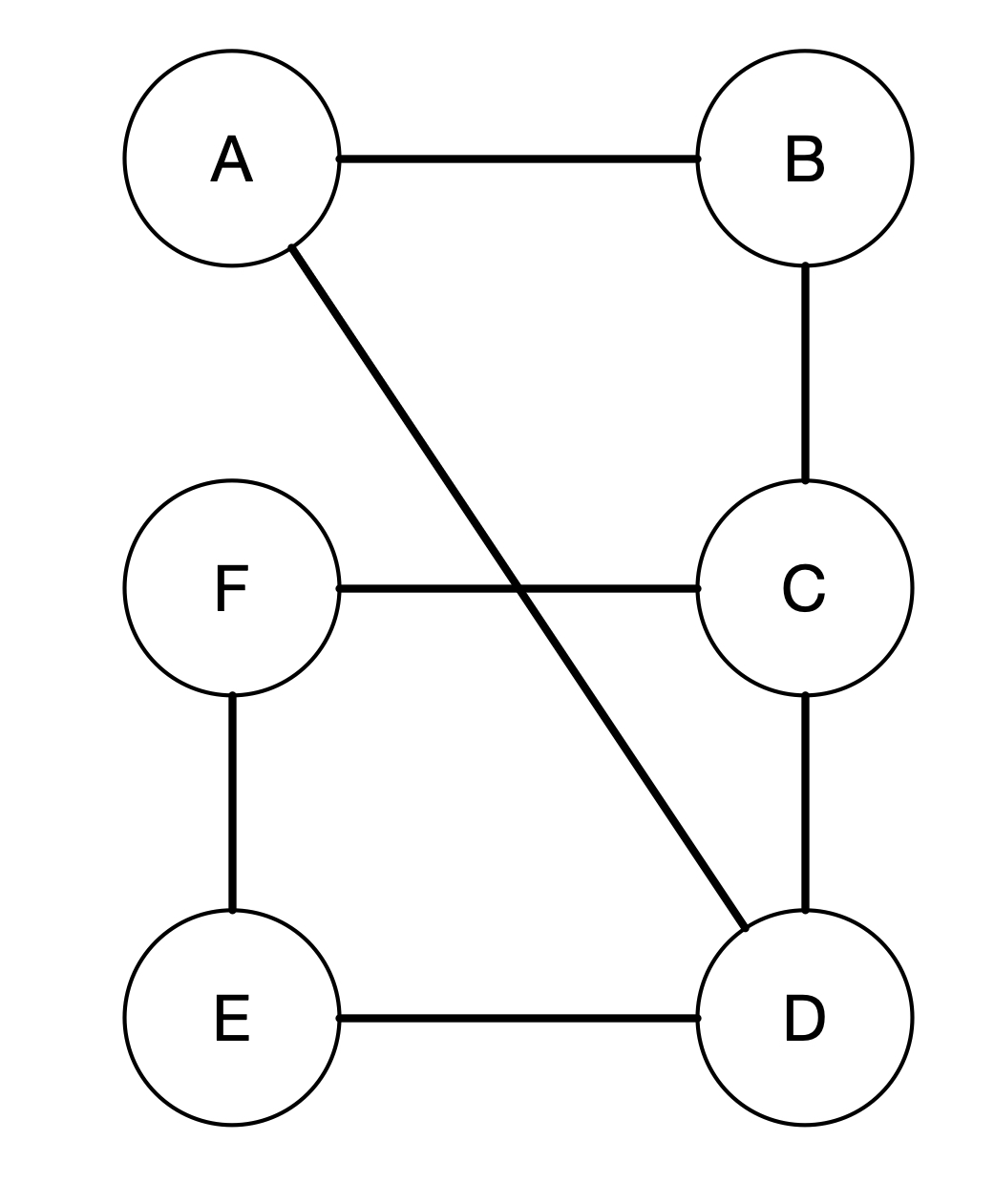

Breadth first search is normally used to find a shortest path between two vertices. For example, when you plan your travel from one point to another point, breadth first search can identify the path you should take that gives the shortest path. How does this work? Let’s take a look at the graph below.

(C)ases

Let’s say we want to find the shortest path from A to F. The way breadth-first search does is to calculate the distance of every vertex from A. So in this case, B will have a distance of 1 since it takes only one step from A to B. On the other hand, C has a distance of 2. D, however, has a distance of 1 since there is an edge from A to D connecting the two vertices directly. Vertex E has a distance 2 because from A it can go to D and then to E in two steps. Finally, F has a distance of 3. There are actually two paths from A to F. The first one is A - B - C - F and the second one is A - D - E - F. Notice that both has the same distance, which is 3.

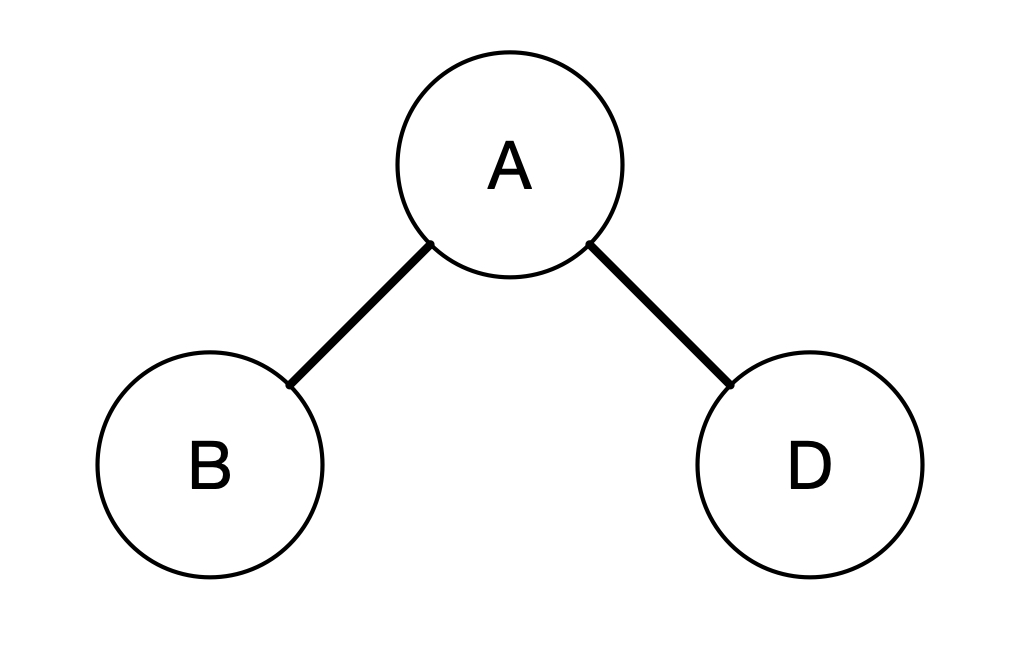

How can we obtain all the distances for each vertex? We will start with the starting vertex which in this case is A. Next, we can look into the neighbouring vertices that A has. So in this case, A has two neighbours, i.e. B and D. We can then explore each of the neighbours. We can draw the the vertex that we are exploring as a kind of a tree.

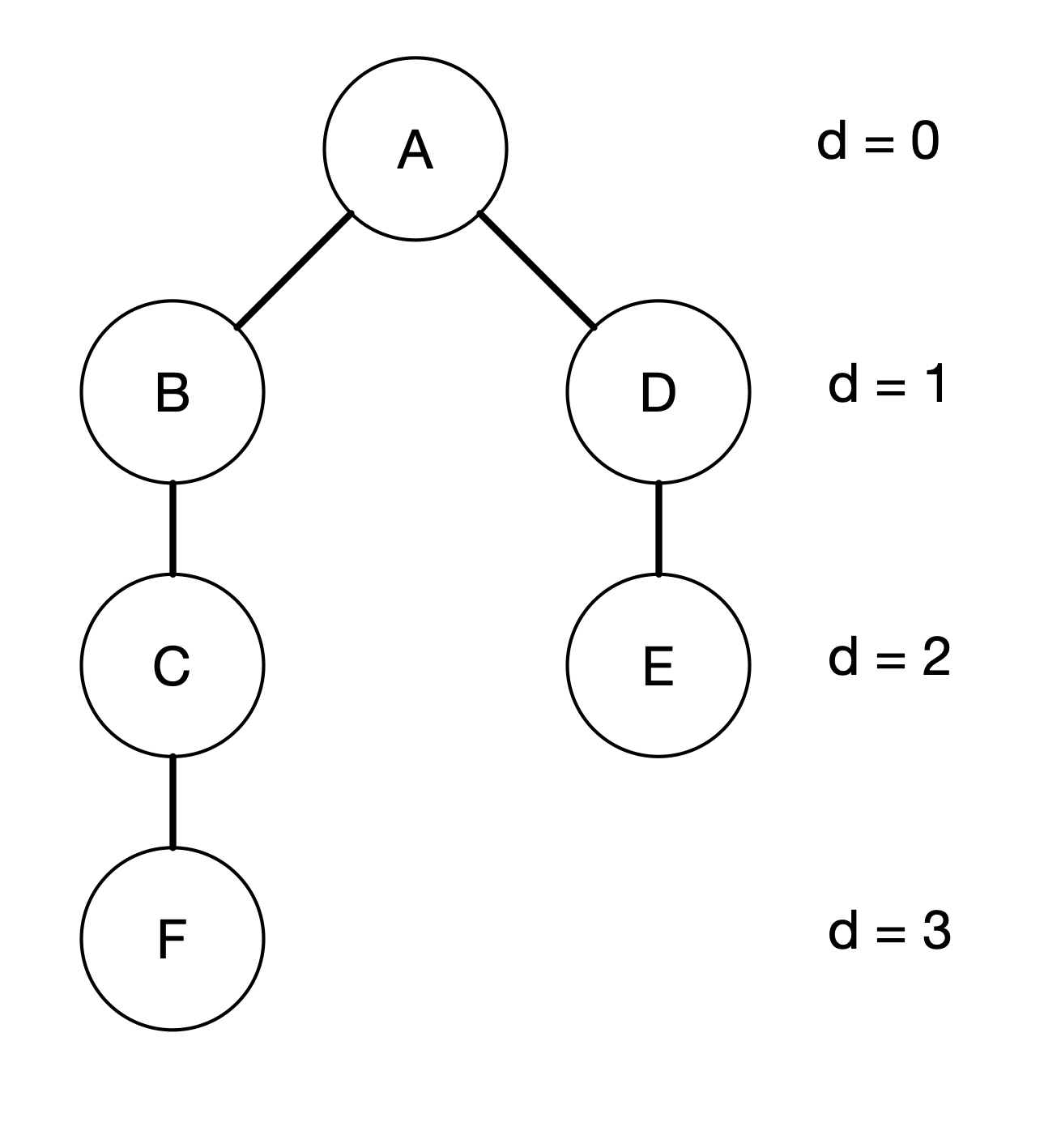

We can then take turn to explore the neighbours of each of the children in the tree. In this case, B has two neighbours, i.e. A and C. But since we have visited A, we do not want to visit A again. So we should only visit C. This indicates that we need to mark the vertices that we have visited. Similarly, D has three children, i.e. A, C and E. But both A and C has been visited, so we should just add E into our tree. We can continue the same steps until all vertices have been visited. The final tree looks like the following.

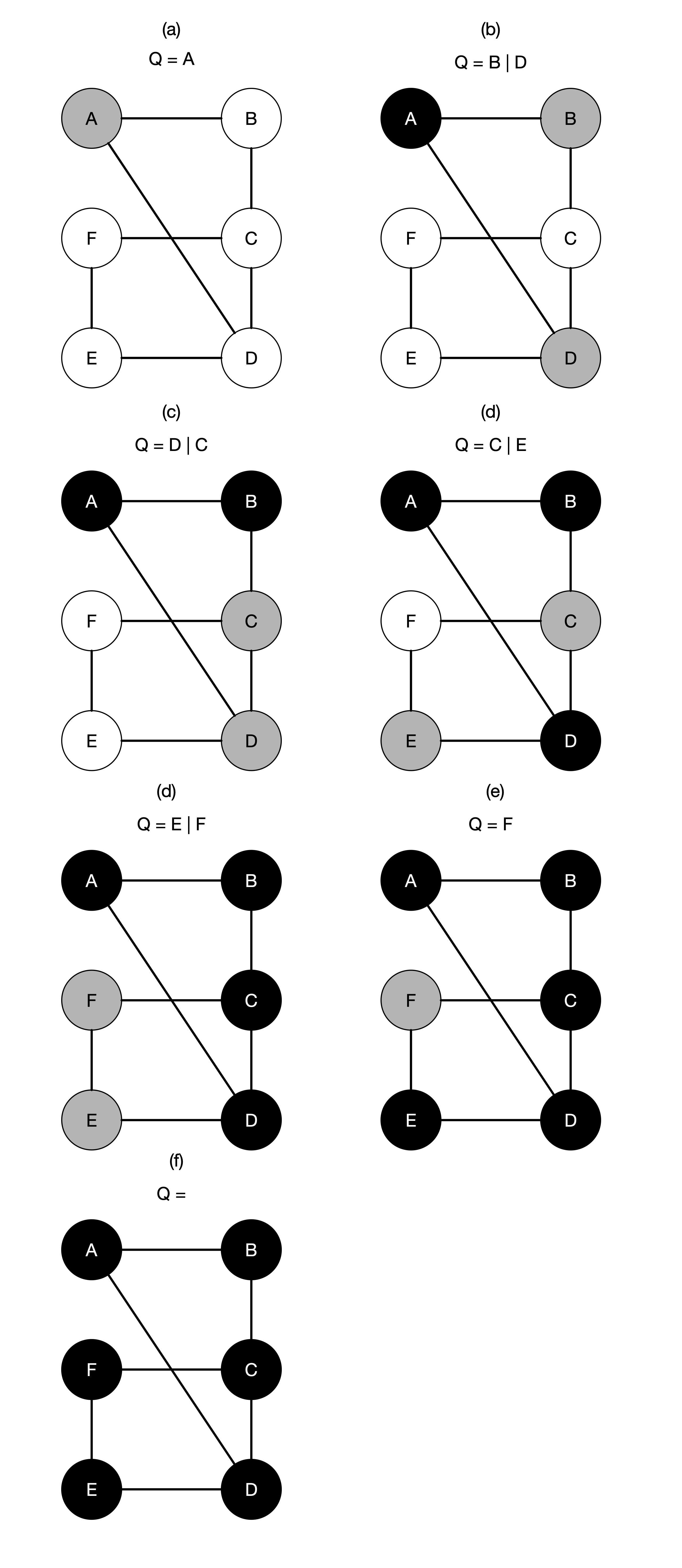

Notice that we can actually add F either to C or to E in the tree above. In this case, we choose to add to C. The question is when do we stop? We should stop when all the vertices have been explored in terms of their children. Therefore, we need some way to indicate if a Vertex’s children have been fully explored. The way we are going to do this is to colour the vertices. Moreover, we are going to use three different colours:

- white: is used to indicate that we have not visited the vertex

- grey: is used to indicate that we have visited the vertex but we have not completely explored all the neighbours

- black: is when we have explored all the neighbours of this vertex.

With this in mind, the image below shows the progression of the vertex exploration and how the colour of each vertex changes.

In the figures above, we use a Queue data structure to explore the vertices. When we visit vertex, we put all its neighbouring vertices into a queue. This also ensures that we explore the vertices in a breadth-first manner. For example, when we explore B from A, we did not go to C but rather D, which is at the same level as B in our search tree. This is where the name breadth-first search comes from. So now we are ready to write our algorithm for breadth-first search.

(D)esign of Algorithm

Input:

- G: Graph

- s: starting vertex

Output:

- Graph with distances on every vertex from s

Steps:

1. Initialize every vertex with the following:

1.1 set color to white

1.2 set distance to INF

2. start from s vertex:

2.1 set s' color to grey

2.2 set s' distance to 0

3. put s into the Queue

4. As long as Queue is not empty

4.1 take out one vertex from Queue and store to u

4.2 for each neighbour of vertex u, do:

4.2.1 if the neighbour colour is white, do:

4.2.1.1 set the neighbour's colour to grey

4.2.1.2 set the neighbour's distance to u's distance + 1

4.2.1.3 put the neighbour into the Queue

4.3 after finish exploring all neighbours, set u's color to black

In the above algorithm, we start by setting all the vertices to white and have a distance of INF or any large number value greater than the number of the vertices. We then start from the vertex s and explore its neighbours. Everytime we explore a neighbour, we check its colour. If the colour is white, it means that it has not been visited previously, so we change the colour to grey and add the distance by one. We then put this neighbour into the queue to visit its neighbours later on. We proceed visiting the vertices by taking out the vertex from the Queue. As mentioned, it is the Queue that ensures that we visit the vertices in a breadth-first manner.

The only thing about this algorithm is that we only get a graph with distances on each vertex, but we would not be able to retrieve the path to take from s to the destination vertex. In order to find the shortest path, we need to store the parent vertex when we visit a neighbouring vertex. To do this, we modify the algorithm as follows.

Input:

- G: Graph

- s: starting vertex

Output:

- Graph with:

- distances on every vertex from s

- parent vertex on every vertex that leads back to s

Steps:

1. Initialize every vertex with the following:

1.1 set color to white

1.2 set distance to INF

1.3 set parent to NILL

2. start from s vertex:

2.1 set s' color to grey

2.2 set s' distance to 0

2.3 set s' parent to NILL

3. put s into the Queue

4. As long as Queue is not empty

4.1 take out one vertex from Queue and store to u

4.2 for each neighbour of vertex u, do:

4.2.1 if the neighbour colour is white, do:

4.2.1.1 set the neighbour's colour to grey

4.2.1.2 set the neighbour's distance to u's distance + 1

4.2.1.3 set u as the parent vertex of the neighbour

4.2.1.4 put the neighbour into the Queue

4.3 after finish exploring all neighbours, set u's color to black

In the second algorithm, we have a new attribute called parent. In the beginning we set all vertices to have NILL as their parents. Since s is the starting vertex, it has no parent and so we set to NILL in step 2.3. We added step 4.2.1.3 where we set u as the parent to the neighbouring vertex when we add that neighbouring vertex into the Queue.

With this, we can write another algorithm to retrieve the path from s to some destination vertex v.

Find-Path BFS Input: - G: graph after running BFS - s: start vertex - v: end vertex Output: - list of vertices that gives the shortest path from s to v Steps: 1. if v is the same as the start vertex 1.1 return a list with one element, i.e. s 2. otherwise, check if parent of v is NILL 2.1 return "No path from s to v exist" 3. otherwise, 3.1 call find-path(G, s, parent of v) 3.2 add v into the result from 3.1

The above algorithm uses recursion. There are two base cases. The first base case is when the destination vertex to be the same as the starting vertex. In this case, the output is just that vertex. The second base case is when there is no path from s to v. We know there is no path when along the path starting from v we find a vertex which parent is NILL. The recursion case is described in step 3. In this case, we call the same function but with the destination vertex to be the parent of the current destination vertex. By moving the destination vertex to the parent, we reduce the problem and make it smaller until we reach base case described in step 1.

Let’s see an example when we search a shortest path from A to F in the previous graph. In this case, v is not the same as s since A and F are two different vertices. So we look into F’s parent, which is C. Now we call the same function to find the path from A to C. Since A and C are different, we look into C’s parent, which is B and call the function to find the path from A to B. Finally, we look into B’s parent and find the path from A to A. This is the base case. When we reach the base case, we return a list containing A as the result (step 1.1). Then we move back and do step 3.2 to add B, C, and finally F. So the shortest path from A to F will be a list [A, B, C, F].

Now it’s time to implement the algorithm. But before we can implement the algorithm, we need to modify the class Vertex to contain a few additional attributes:

- colour

- distance

- parent

As mentioned in the Introduction, we will do this using the concept of Inheritance.

Inheritance

Inheritance is an important concept in object oriented programming that allows us to re-use existing code or classes we have written. In our example here, we already have a class Vertex and Graph. However, the class Vertex only contains id and neighbours.

As shown in the previous section, our Vertex object has additional attributes such as colour, distance, and parent. We can actually create a new class containing all these new properties as well as the commonly found properties of a vertex (id and neighbours). However, we will duplicate our codes and rewriting the methods that is the same for all Vertex objects such as adding a neighbour. Inheritance allows us to create a new class without duplicating all the other parts that is the same. By using inheritance, we create a new class by deriving it from an existing base class. In this example, we can create a new class called VertexSearch that is derived from a base class Vertex. When a class inherits another class, the new class possess all the attributes and methods of its parent class. This means that VertexSearch class contains both id and neighbours as well as all the methods that Vertex class has. What we need to do is simply to specify what is different with VertexSearch that Vertex class does not have. We can represent this relationship using a UML diagram as shown below.

In the UML diagram, the relationship is represented as an arrow with a white triangle pointing from the child class to the parent class. This relationship is also called is-a relationship which simply means that VertexSearch is-a Vertex, it has all the attributes and methods of a Vertex object.

In Python, we can specify if a class derives from another class using the following syntax:

class NameSubClass(NameBaseClass):

pass

For our example here, we can write the VertexSearch class as follows.

class VertexSearch(Vertex):

pass

In the above class definition, we have Vertex inside the parenthesis to indicate to Python that we will use this as the parent class or base of VertexSearch class. In this new class, we can initialize all the new attributes as usual:

import sys

class VertexSearch(Vertex):

def __init__(self, id=""):

super().__init__(id)

self.colour = "white"

self.d = sys.maxsize

self.parent = None

Notice here that we initialize:

colourto be “white”dto be a large integer numberparentto be aNoneobject

The first line super().__init__(id) is to call the parent class’ initialization method to initialize the both the id and the neighbours. The word super comes from Latin which means “above”. Therefore, super() method returns a reference to the parent’s class. Since we have both __init__() method in VertexSearch and Vertex, we need to be able to differentiate the two methods. For this purpose, Python provides super() method to refer to the parent’s class methods instead of the current class.

In the child class VertexSearch we redefine the __init__() method of the parent’s class. This is what is called as method overriding. We will discuss more of Inheritance in future lessons.

Depth-First Search

There is another kind of search that can be done on a graph. This is called depth-first search (DFS). As the name implies, this algorithm explores the neighbouring vertices in a depth-wise manner. DFS is used in topological sorting, scheduling problems, cycle detection in graph and solving puzzles with only one solution such as finding a path in a maze or solving a sudoku puzzle. Let’s illustrate this with the same graph as we have seen previously.

(C)ases

In depth-first search, we go down the tree before moving to the next siblings. For example, as we start from A, we look into its neighbouring vertices. So vertex A has two neighbours, i.e. B and D. The depth-first search algorithm will visit one of them, say vertex B. After it visits B, it will explore one of the neighbours of B instead of visiting D. This is illustrated below.

In the figures above, every time we visit a vertex, we put a timestamp on that vertex called discovery time. Once we finish visiting all the neighbours of that vertex, we put another timestamp called finishing time. For example, vertex A has a discovery time 1 and finishing time 12 as indicated by 1/12 in the figure.

We also labelled the edges with two different kind of symbols. The solid line edges are called tree edges. These are edges in the depth-first forest. An edge (u, v) is a tree edge if v was first discovered by exploring edge (u, v). For example, the edge (A, B) is a tree edge since B is first discovered by exploring the edge (A, B). On the other hand the edge (A, D) is not a tree edge since D was not first discovered by exploring edge (A, D). Rather, D was first discovered by exploring the edge (C, D).

This brings us to the other kind of edges discovered by depth-first search. The dashed line edges are called back edges. These are those edges connected a vertex u to an ancestor v in a depth-first tree. For example, A is an ancestor of D. We can see that because we explore D through A - B - C - D. So the edge connecting D to A is a back edge since it connects D to one of its ancestor. Similarly with the edge (C, F). The depth-first forest is shown below.

(D)esign of Algorithm

Now we can try to write the steps to do depth-first search. We will write the steps using two functions. The first one is called DFS as shown below.

DFS

Input:

- G: graph

Output:

- G: graph with the following attributes marked

- colour

- discovery time

- finishing time

- parent

Steps:

1. Initialize each vertex as follows:

1.1 set colour to white

1.2 set parent to NILL

2. set time to 0

3. for each vertex in the graph G

3.1 if the vertex's colour is white, do:

3.1.1 dfs-visit(G, u)

The above algorithm simply initialize the vertices and go through every vertex to perform the second function DFS-VISIT.

DFS-Visit

Input:

- G: graph

- u: vertex to visit

Output:

- G: graph with the following attributes marked

- colour

- discovery time

- finishing time

- parent

Steps:

1. increase time by 1

2. set current time to be the discovery time for u

3. set u's colour to gray

4. for each vertex in u's neighbours, do:

4.1 if the vertex's colour is white, do:

4.1.1 set u as the parent of the vertex

4.1.2 call dfs-visit(G, the current vertex)

5. set u's colour to black

6. increase time by 1

7. set current time to be the finishing time

This function simply set the discovery time for the visited vertex u and begins to visit all the neighbouring vertices of u. However, it only calls DFS-VISIT if the neighbouring vertices are white, which means these vertices have not been visited yet. Once it finishes visiting all the neighbouring vertices, it marks the vertex u to be black and set the finishing time.

Topological Sort

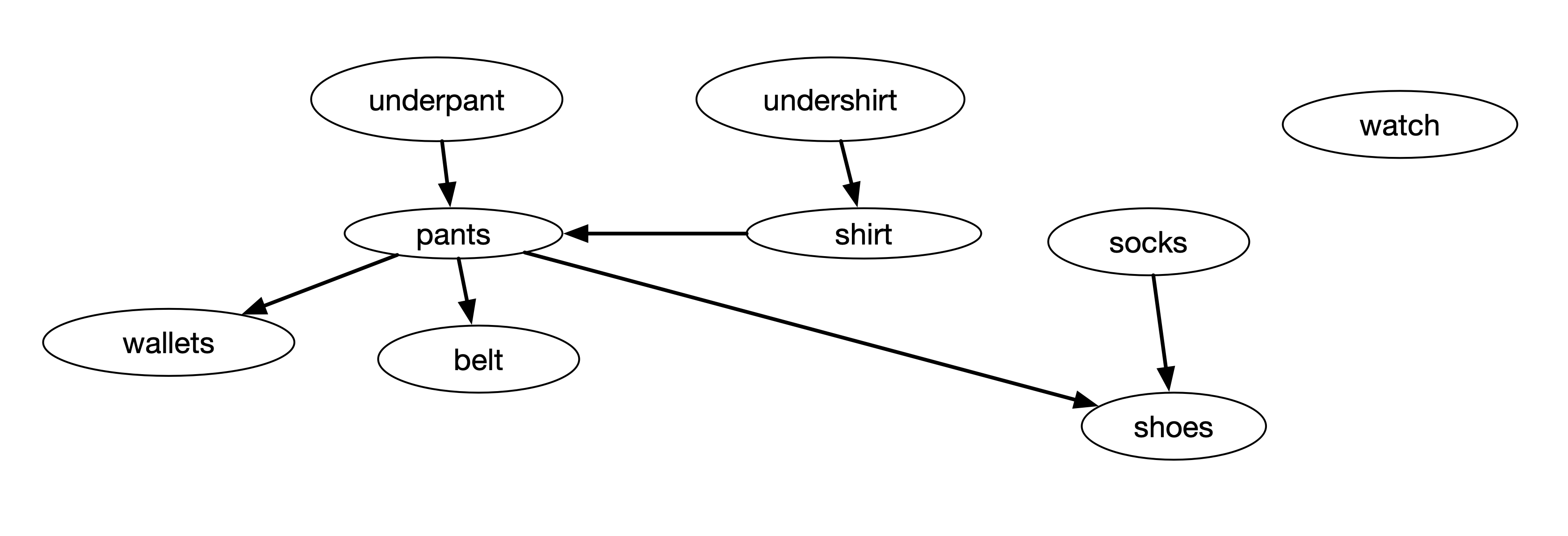

One application of depth-first search algorithm is to perform a topological sort. For example, if we have list of task with dependencies, we can sort which task should be performed first. The figure below gives an example of this dependencies tasks

The figure above shows a directed graph of dependencies between different tasks. For example, the task wearing a pant must be done only after the task of wearing underpant and wearing a shirt. We can use the finishing time of DFS to determine the sequence of tasks.

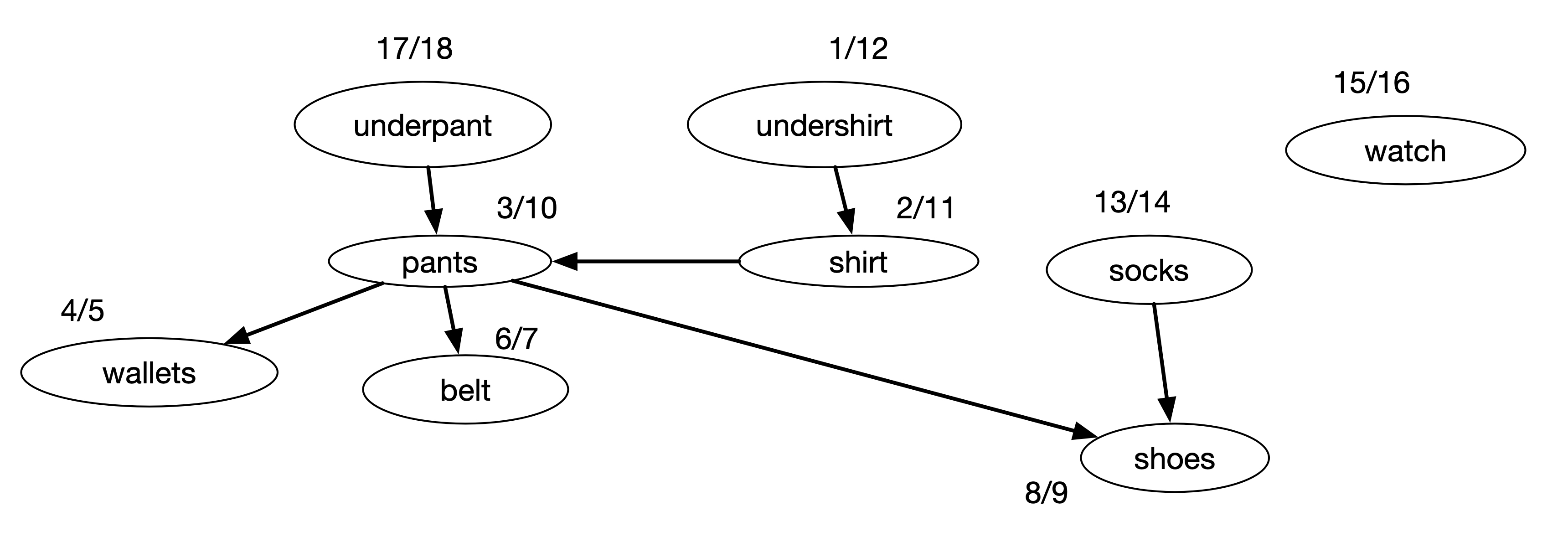

Let’s try to perform DFS for the above graph. The discovery time and the finishing time for each task is shown in the figure below.

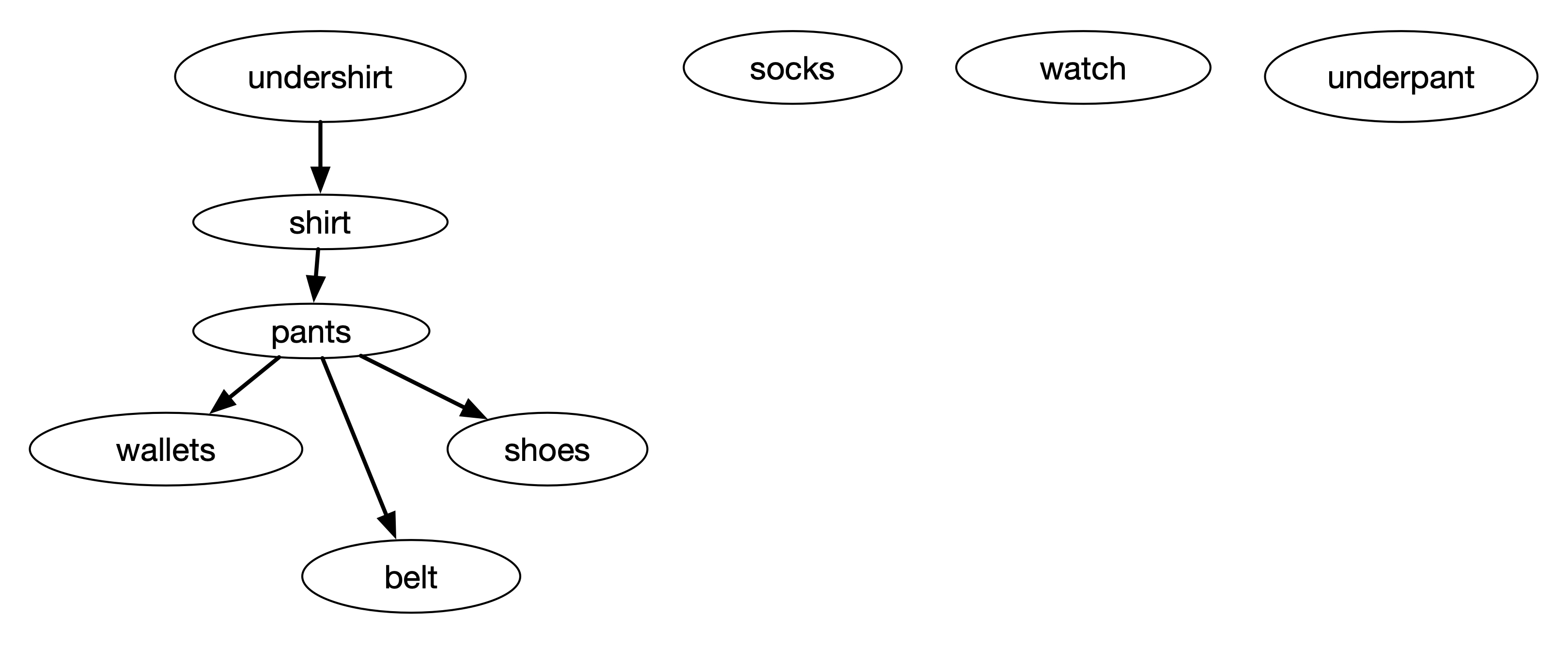

In the process of DFS, it somehow starts with “undershirt” and traverse to all the children vertices in the tree, i.e. “pants”, “wallets”, “belt”, and then “shoes”. After this, it creates another tree starting from “socks”, and then another tree starting from “watch”, and finally another tree starting from “underpant”. The depth-first forest looks like the figure below.

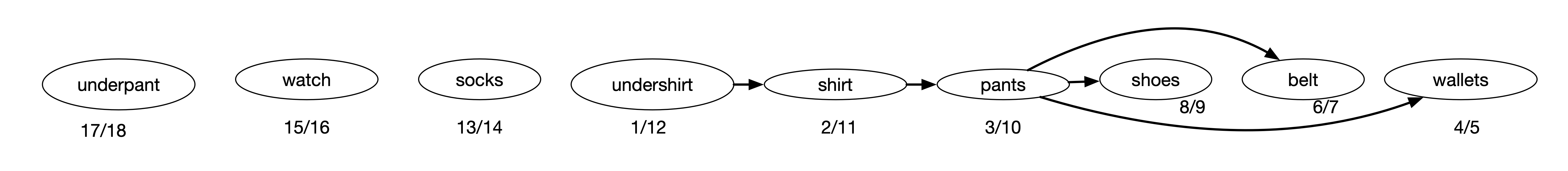

We can re-order the tasks by its finishing time from the largest to the smallest as shown in the figure below.

The sequence above is based on its finishing time from the largest to the smallest. The first three are independent and their sequence can be interchanged, but subsequently, “shirt” must be done only after “undershirt” task. This sequence may also depends on which vertex the search encounters first. With this in mind, we can write the topological sort steps as follows.

Topological-Sort Input: - G: graph Output: - list of sorted vertices Steps: 1. call DFS(G) to compute the finishing time for each vertex in G 2. sort the vertices based on its finishing time from largest to smallest 3. return a list of sorted vertices