By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Define a state machine

Important words:

- state machine

- start state

- pure function

- state transition diagram

- time step table

State Machine as a Function

In the first few weeks, we do computation by defining a function. When the computation return a value, we can write its output in terms of a mathematical equation as shown below.

\[o = f(i_1, i_2, \ldots)\]In the above expression, we notice that the output is a function of the different inputs, i.e. $i_1, i_2, \ldots$. We call it Pure Function if the output only depends on the current input. Mathematically, we can express this as

\[o_t = f(i_t)\]which says that the output at time $t$ is a function of the input at time $t$. We can express a state machine as a computation machine where the output is not only the function of the current input, but also a function of all the previous inputs.

\[o_t = f(i_t, i_{t-1}, i_{t-2}, \ldots)\]The above expression says that the current output at time $t$ is a function of the current input at time $t$ and all the previous inputs. Saying that it is a function of the previous input also means that the current output is a function of some history of the machine. This history of the machine can be captured as a single entity called a state of the machine. Therefore, we can write it as follows.

\[o_t = f(i_t, s_t)\]The above expression states that the current output is a function of the current input and the current state. The history of the machine is captured in the current state of the machine.

Examples of Pure Functions

Let’s illustrate the above definition with some Python programs. We will start with a simple example of a function where the output is just the function of the current input. One example is a function to calculate the cartessian distance of a three dimensional coordinate. Given the three input of x, y, and z, the function returns an output of the distance from the origin.

import math

def distance(x, y, z):

return math.sqrt(x * x + y * y + z * z)

assert distance(3, 4, 0) == 5

Another example is a function that returns true if all the inputs are true. This is actually what a combinational logic (memoryless) AND gate is. We can implement this combinational logic AND gate as a function as shown below.

def multiple_and(*args):

for truth in args:

if not truth:

return False

return True

assert not multiple_and(True, True, False)

assert multiple_and(True, True, True, True)

The two functions above has an output that is a function of only the current input. How about a state machine? What kind of computer program can be called a state machine?

Objects and State Machine

Let’s begin by creating a simple state machine called a light box. A light box has one input which is a button. When the input is pressed, a value of integer 1 is sent to the machine. When the input is not pressed, a value of integer 0 is registered. The machine only has one single button. To turn on the light, one has to press the button one time. To turn off the light, the same button has to be pressed one more time.

Notice that now the output is not just a function of the current input. The input is 1 for both to turn on and off the light. We have to know how many time the input is 1 to determine whether the light is on or off. If the input is 1 only one time and assuming the light is off initially, we should turn on the light. But if the input is 1 for the second time, we should turn off the light.

How can we write a program to simulate this state machine?

One easy way is to use Object Oriented Programming. In this case, the machine is an object and we try to identify, what are its attribute and its methods. In our design, we will have an attribute called state to remember whether the light is currently on or off. We then have a method to set the output of the state machine based on the input. Lastly, we have another method called transduce() that takes in an argument which is a list of the input for different time steps. We write our class definition below.

class LightBox:

def __init__(self):

self.state = "off"

def set_output(self, inp):

if inp == 1 and self.state == "off":

self.state = "on"

return self.state

if inp == 1 and self.state == "on":

self.state = "off"

return self.state

return self.state

def transduce(self, list_inp):

for inp in list_inp:

print(self.set_output(inp))

lb = LightBox()

lb.transduce([0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1])

off

off

on

on

on

on

on

off

on

off

on

on

off

The test code in the above example call the transduce method with a list of integer values. The input is 1 when the button is pressed and 0 otherwise. We can see that when the button is pressed at time step 3, the output changes from “off” to “on”. Notice that initially the output is “off”. At time step 8, we have 4 presses of the input buttons and we can see the output is toggled four times. At the last time step, the button is pressed again and the light is switched from “on” to “off”. We have implemented our first state machine.

In general, we can say that all objects in a computer program is a state machine where the values of the objects’ attributes define the state of those objects.

Next State Function

In the previous example of light box state machine, it happens that the output is always the same as the state. But this is not necessarily the case. The output can be different from the state. So in general, a state machine has two functions: the output function and the next state function.

\[o_t = f(i_t, s_t)\] \[s_{t+1} = f(i_t, s_t)\]The first one is the output function which we have discussed. The second mathematical expression expresses the next state function of the state machine. It simply says that the next state of the machine is a function of the current input and the current state.

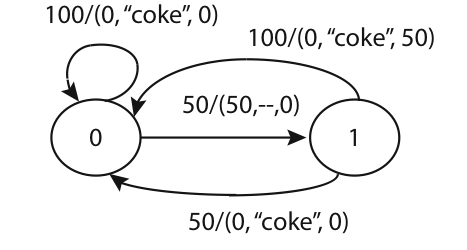

To illustrate that the output function can be different from the next state function. Let’s consider a new state machine called the Coke Machine. The figure below shows what we call as the state transition diagram. There are many possible design of a Coke machine and the one below is just one particular example of our design choice.

Each directed arc in the state diagram is labelled as $x/y$ where $x$ denotes the input received and $y$, the output generated. For example, the arc that connects state 0 to state 1 that’s labelled 50/(50, ’--’,0) means that when the dispenser receives 50¢ (50 before the /) in state 0, it moves to state 1 and generates an output of (50, ’--’,0). This tuple of values in the output indicates that the dispenser display shows 50 which is the amount deposited by the user, no coke has been dispensed yet as indicated by --, and no change has been returned to the user as indicated by the last entry which is a 0.

The machine accepts only 50¢ and one dollar (100¢) coins. It has a display that shows how many cents have been deposited.

The above state machine has only two states, 0 and 1. State 0 is when there is no coin deposited inside the machine while state 1 is when there is a 50¢ deposited inside the machine. The output, however, has more than two possible outcomes. The output is expressed as a tuple of three values (x, y, z):

- the first part, x: is the amount of money inside the machine.

- the second part, y: is the status whether coke is dispensed or not.

- the third part, z: is the change output of the machine.

The state transition diagram is a visual way of defining the output function and the next state function. By looking at the state transition diagram and knowing where the current state is, one can determine both the output and the next state of the machine.

Initial State

What is lacking in the above diagram is the information of the initial state. A state transition diagram should also contains the information which is the initial state of the machine. In the above case, it makes sense to set state 0 as the initial state where there is no money being deposited into the machine.

Without information on the initial state, we cannot determine either the output nor the next state. It is important, therefore, to indicate which is the initial state of the machine.

Abstracting a State Machine

As we can see that all state machines must store information about their states. For example, the light box needs to remember whether currently it is on or off and a coke machine needs to remember whether it contains a 50 cents inside the machine or not. Moreover, every state machine must be able to determine its output and next state from the current input and the current state. This is true for both light box and coke machine. The difference is that in light box machine, its output function is the same as the next state function. On the other hand, the coke machine output function is not the same as the next state function. Regardless of these two functions, a state machine should be able to move to the next state at every time step. Since all state machines have some common property and functionality, it is possible to abstract these in OOP with an Abstract Base Class. We will show this in the next lesson.