By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Inherit a class to create a child class

- Explain

is-arelationship - Draw UML diagram for

is-arelationship - Override operators to extend parent’s methods

- Implement Deque data structure as a subclass of Queue

Important words:

- inheritance

- child class

- parent class

- super

- override

- abstract base class

- iterable

Inheritance

In the previous lesson, we have shown that we can reuse the code from some base class by using inheritance. The syntax in Python for deriving a class from some base class is as follows:

class NameSubClass(NameBaseClass):

pass

The name of the parent class or the base class is specified in the parenthesis after the class name. By specifying this, the child class inherits all the attributes and methods of the parent class. So what do we define in the child class? We can define the following things:

- attributes and methods that are unique to the child class

- methods in the parent’s class that we want to override

One example that we had in the previous lesson is to create the class VertexSearch from the class Vertex. The class Vertex has two attributes: id and neighbours. When the class VertexSearch inherits from Vertex, any object of VertexSearch also has id and neighbours. What we need to define in the class VertexSearch are those attributes not present in the parent class. In this example, VertexSearch has additional attributes of colour, distance, and parent. Now, Vertex in general will not have these attributes since these are only used when doing a graph search. Similarly, we can also define any additional methods in the child class that is present in the parent class.

Besides defining attributes and methods that are unique to the child class, we can also re-define the methods of the parent class. This is what is called as overriding. One common method that is usually overridden is the initialization method.

class Vertex:

def __init__(self, id=''):

self.id = id

self.neighbours = {}

And the class VertexSearch can override this initialization:

import sys

class VertexSearch(Vertex):

def __init__(self, id=""):

super().__init__(id)

self.colour = "white"

self.d = sys.maxsize

self.f = sys.maxsize

self.parent = None

The first line of the init is to call the parent class’ initialization and the subsequent lines proceed to initialize those attributes that is unique to the child class. In this way, we need not re-write all the initialization codes of the parent class and simply re-use them. Note that in overriding a method in the parent class, we use the same method’s name and arguments as in the parent class.

Let’s discuss a few more examples of inheritance.

Fraction and MixedFraction

Let’s say we have a class called Fraction which has two attributes: numerator and denominator. This class also has all the methods to do the operation such as addition and subtraction. With this we can do addition and subtraction of Fraction:

f1 = Fraction(1, 2)

f2 = Fraction(3, 4)

f3 = f1 + f2

f4 = f2 - f1

The first line creates a fraction object $1/2$ while the second line creates a fraction object $3/4$. The third line adds these two fractions $1/2 + 3/4 = 5/4$ which is then stored in f3. The last line, on the other hand, subtracts these two fractions, $3/4 - 1/2 = 1/4$ which is then stored in f4.

What should we do if we want to do operation with a mixed fraction such as the following?

\[1 \frac{1}{2} + 2\frac{3}{4}\]Well, we can always represent these mixed fraction as two ordinary fractions

\[\frac{3}{2} + \frac{11}{4}\]and perform the same fraction operations. However, we do not want to do this manipulation or conversion manually if we can just write a computer code to do so. Therefore, it is worthwhile to create a new class called MixedFraction where we can define a fraction that may contain a whole number and additional numerator and denominator. What is different from the Fraction class is the way we initialize this object. Using the example above, i.e. $1 \frac{1}{2} + 2\frac{3}{4}$, we want to be able to write in the following manner:

f1 = MixedFraction(1, 2, 1)

f2 = MixedFraction(3, 4, 2)

f3 = f1 + f2

Note that we purposely put the whole number as the last argument because we want MixedFraction to be able to handle ordinary fraction when the whole number is zero.

f4 = MixedFraction(1, 2) # this is the same as Fraction(1, 2)

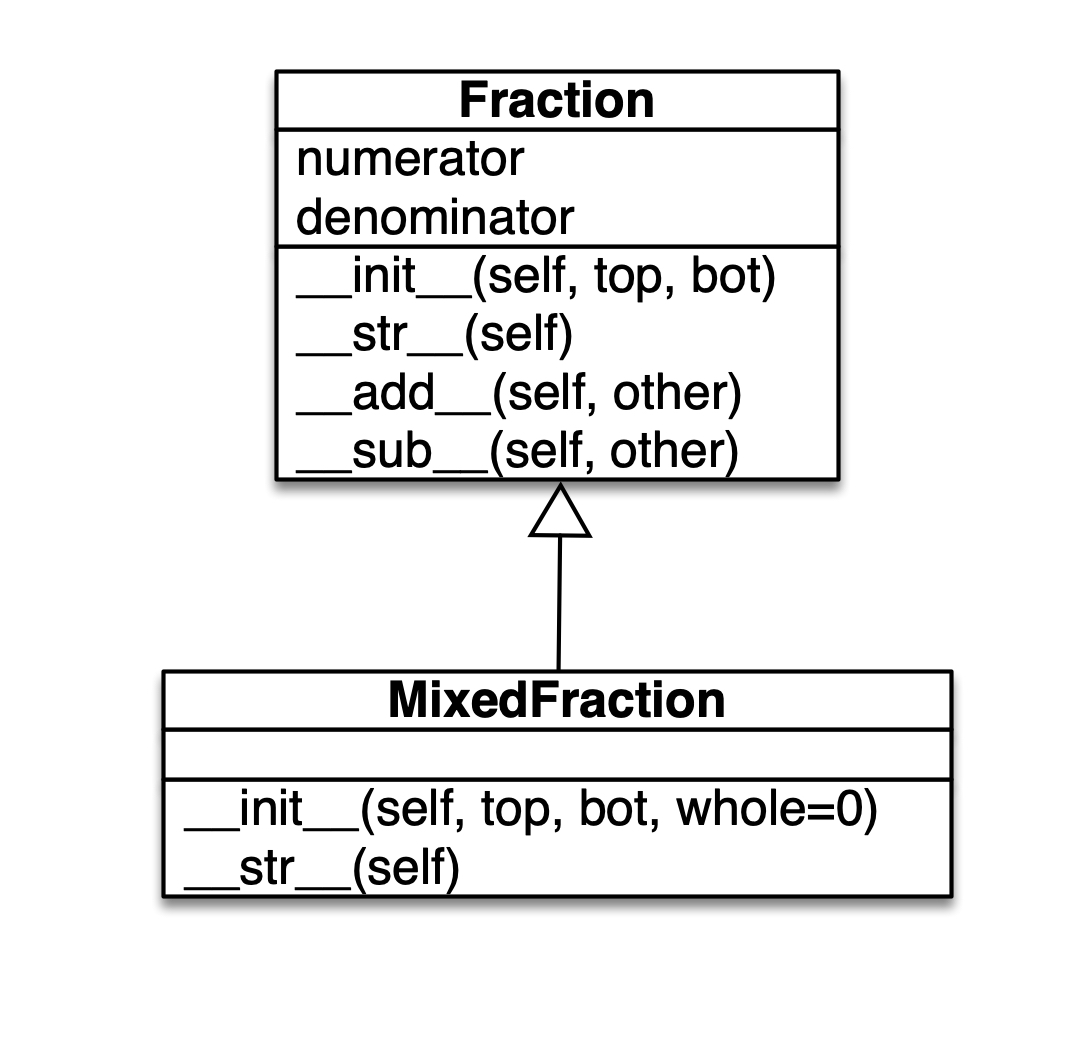

The UML class diagram can be seen as shown below.

In the above UML diagram, we choose not to have any additional attributes but only different initialization arguments. This means that we have to initialize the numerator and the denominator from the three arguments used in the initialization MixedFraction(top, bottom, whole), i.e.

Similarly, there are no methods to do addition and subtraction. The object of MixedFraction depends on its parent class’ methods to do addition and subtraction. In fact, when Python cannot find the name of a particular method in the child class, it will try to find the same name in the parent class’ methods. If no name is matched in the parent class’ methods, Python will throw an error saying that such method is not defined.

Moreover, we also choose to implement __str__() method which is called whenever Python tries to convert the object to an str representation. Notice that we choose to override this method in the child class. The reason is that we want Fraction and MixedFraction to be represented differently as a string. For example, $5/2$ will be represented differently depending whether it is a Fraction object or a MixedFraction object.

5/2 # str representation of Fraction

2 1/2 # str representation of MixedFraction

This is an example of how a parent class’ method is overriden in the child class. The name and the argument of the method is the same and yet the behaviour is different in the child class.

Now, let’s look at another example

Queue and Deque

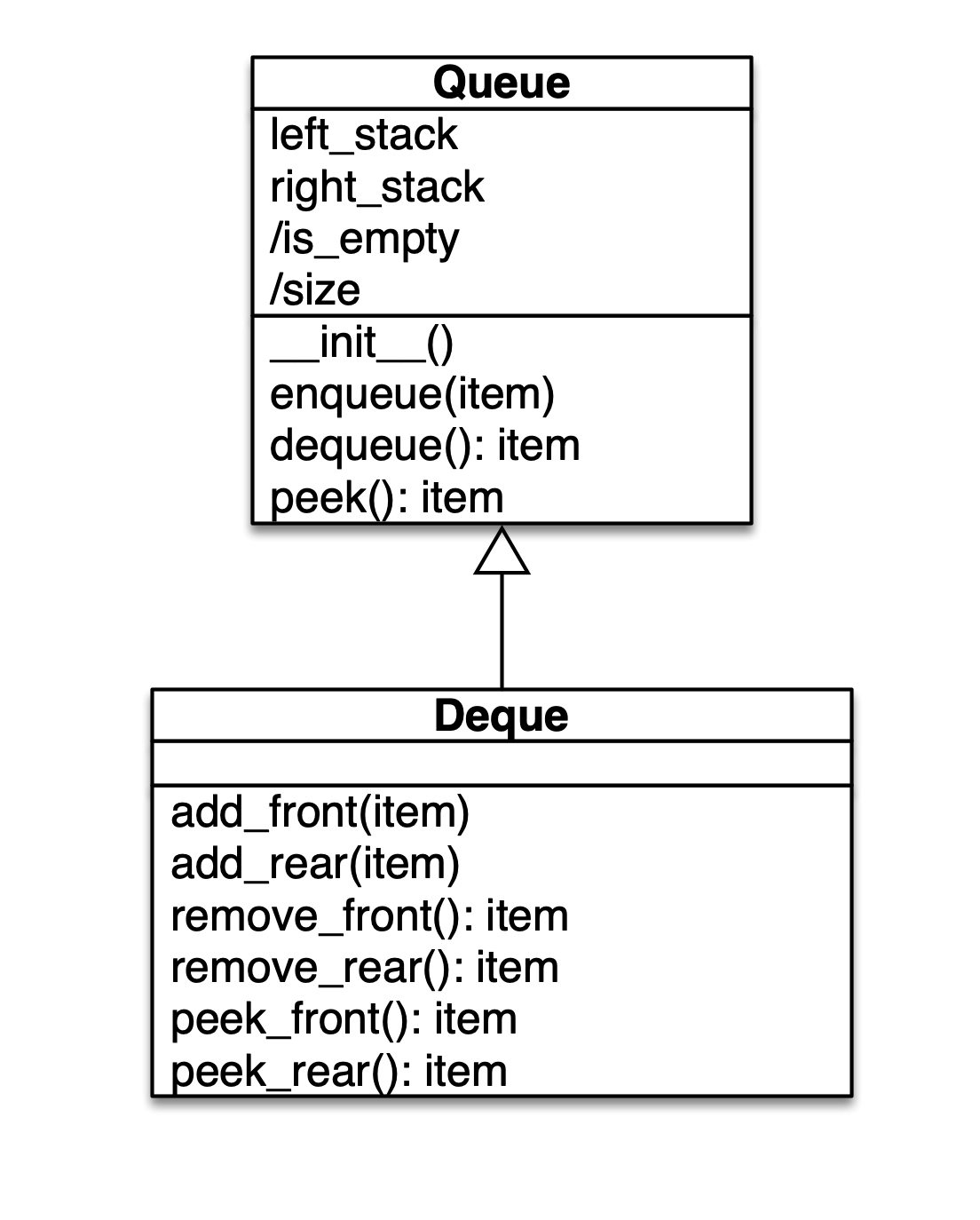

Another example we can work on is to extend the class Queue to implement a new data structure called Deque (pronounced as deck). The difference between a Queue and a Deque is that in Queue the item only has one entrance which is from the back of the Queue. The exit of a Queue object is at the front of the Queue. On the other hand, a Deque can be inserted other from the front or from the rear. Its item also can be popped out from either the front or the rear. Below is the UML representation of the class diagram when Queue is implemented using a double Stack.

Notice that in the above UML class diagram, we use / to represent computed property, i.e. /size and /is_empty. Deque does not have any additional attributes or property. The only changes are the methods. We rename and add additional methods for Deque class. In this cass, add_rear(item) of Deque is the same as enqueue(item) of a Queue object. Similarly, remove_front() method of Deque is the same as dequeue() of a Queue object. This is also true for the case of peek_front() and peek(). Thus, we need not re-write half of the methods in Deque class since we can simply call its parent class’ methods.

Abstract Base Class

There are cases when the parent class only specifies what attributes and methods the child classes should have and in itself contain no implementation. You can think of this as something like the following definition:

class MyAbstractClass:

def add(self, other):

pass

class ChildOfMyAbstractClass(MyAbstractClass):

def add(self, other):

# contains implementation of adding the two objects

...

In the first class of MyAbstractClass, there is a method add(other) which contains no definition. This method is overriden by the child class ChildOfMyAbstractClass. In this class, add(other) is defined and, thus, overridden.

Previously in MixedFraction class, we see how the child class’ operations depends on the implementation of its parent class’ methods. In that case, no __add__() nor __sub__() is defined in the child class. Therefore any method call to do addition and subtraction will be referred to the parent class implementation. The case of an Abstract class is the opposite of this. When we have an Abstract class with no implementation, we are forcing the implementation to be found in the child class. However, by writing the code as shown above, there is nothing that prevents the child class not to implement the required method.

Python provides some mechanism to ensure that the abstract method in the abstract base class is implemented in the child class. Let’s take a look at one example of this using collections.abc class. This collections.abc class is an Abstract Base Class for containers. For example, if we want to create a new data type belonging to a type Iterable, we can inherit this new class from collections.abc.Iterable. Python will force the new class to define the method __iter__(). Otherwise, Python will throw an error. Let’s try it out in the next cell.

import collections.abc as c

class NotRightIterable(c.Iterable):

def __init__(self):

self.data = []

test = NotRightIterable()

The output is

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-3-04bbdf83346f> in <module>

5 self.data = []

6

----> 7 test = NotRightIterable()

TypeError: Can't instantiate abstract class NotRightIterable with abstract methods __iter__

When you run the above cell, Python will complain saying that it cannot instantiate the new class because we did not implement the abstract method __iter__(). To fix this, we need to define this method in the child class.

import collections.abc as c

class RightIterable(c.Iterable):

def __init__(self):

self.data = []

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self.data)

test = RightIterable()

There will be no error when you run the above cell because now the method __iter__() has been implemented in the child class. The definition of __iter__() simply returns an iterable object from self.data.

So, we have shown the mechanism where Python ensures that when you create an Abstract Base Class with some abstract methods, the child class must implement this abstract method. Otherwise, Python will throw an exception. In future lessons, we will create our own Abstract Base Class.

Abstract Base Class for Creating Abstract Data Types

We can apply this concept of Abstract Base Class to implement Abstract Data Type (ADT). ADT is a data type for objects whose behaviour is defined by some specific interface. The interface defines the operations that the data type can perform. However, ADT does not define how these operations are to be implemented. It is called abstract because it is independent of its implementation.

As an example, we can create an Abstract Data Type (ADT) for a List object. In this list object, we can specify a set of operation as its interface. This operations specifies what List ADT can do. For example, here are some common List operations we can think of:

- a List object an access an element in the list using its index.

- a List object can modify an element in the list given its index.

- a List object can append an element into the list.

- a List object can remove an element given its index position.

- a List object can check the number of elements in the list.

As mentioned previously, ADT does not specify how to implement these operations nor how to implement the data structure underlying it. ADT only specifies its interface by stating what are the operations that this data type should be able to do. Why is this important? The reason is that certain implementation may be better for specific scenario while other implementation maybe be better for other scenario.

Let’s give some example to this. Let’s imagine if our List ADT is implemented using Python’s built-in list. We know from Python computational model that the following holds true for the complexity of the following operations.

append(item)andpop()has complexity of $O(1)$.- on the other hand,

insert(0, item)has complexity of $O(n)$.

Imagine if our use case has more operations to insert at the beginning of the List. In this case, Python’s built-in list may not be the best implementation. Another implementation like Linked List maybe better. We will discuss about Linked List in the next section. But for now, we see that different implementation may have different performance. However, the operations for List remain the same. Regardless of how it is implementated, we still want to insert the item or remove it.

Therefore, it is useful to define an Abstract Base Class that specifies the interface of an Abstract Data Type. In our case, we can define that a List must have some specific operations that it has to support such as appending, inserting and removing elements. The Abstract Base Class may not have the full implementation and yet it specifies that it request some of these methods to be implemented in the child class.

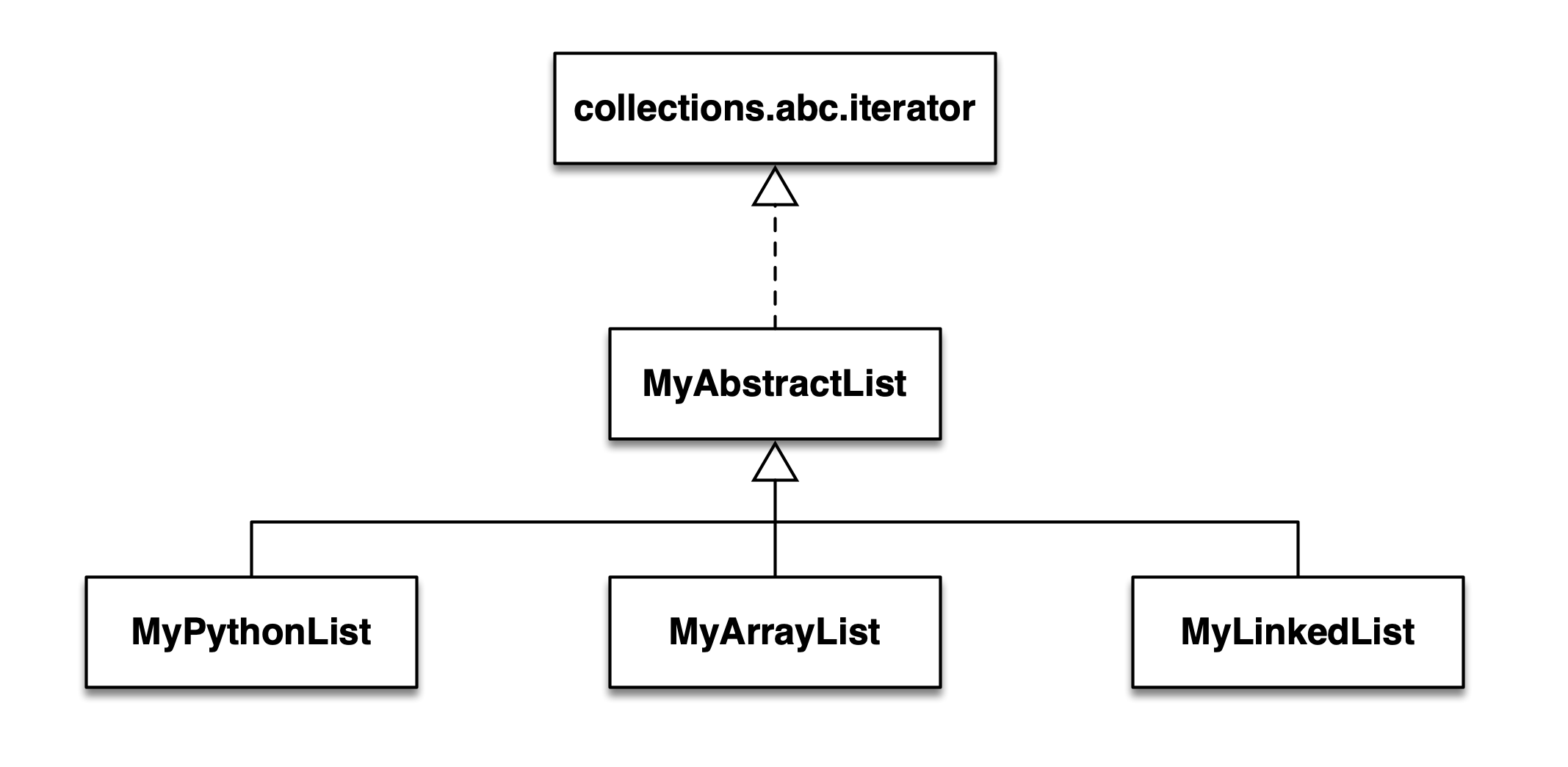

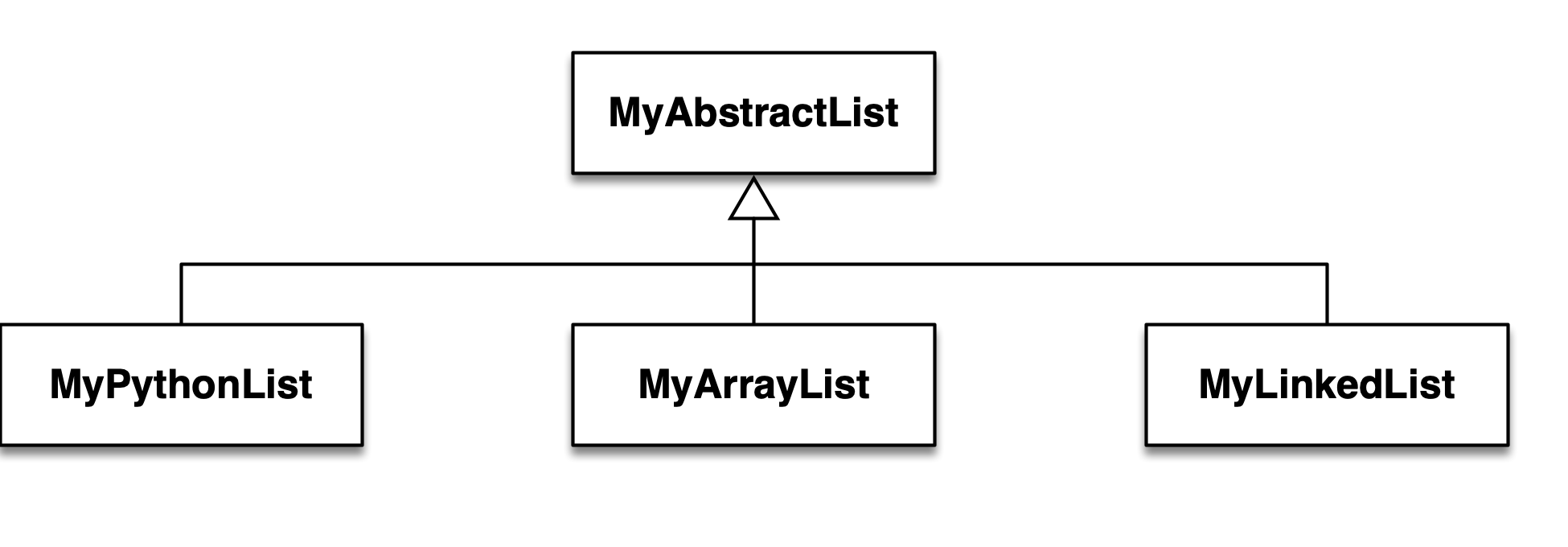

We can then design an abstract base class for our List data as shown in the image below.

In this design, we have one abstract base class called MyAbstractList which defines the interface for our List ADT. This base class can be implemented in many ways. In your problem sets, you will implement this List ADT using a Fixed Size Array (MyArrayList) as well as using a Linked List (MyLinkedList). Details on the Fixed Size Array and Linked List is given in the next section. We gave you the implementation the List ADT using Python’s built-in List (MyPythonList) in the problem set.

The great thing is that all these three different implementation has a common interface and a same set of methods. This way, you can switch your List implementation and the rest of the code still works fine because it follows the common interface of our MyAbstractList ADT. In this case, our abstract base class MyAbstractList enforces that the child class has to implement some specific methods. Extending this concept further, we can actually inherit MyAbstractList from collections.abc.Iterator. In this way, we enforce that our List ADT must have the __iter__() method. This allows our List ADT to be iterated over each of its elements. We can draw the final UML diagram in this way.